The Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle is a fascinating and mysterious member of the marine turtle family. As the smallest of all sea turtles, it stands out not only for its size but also for its rare and dramatic nesting behavior known as an arribada, where hundreds of females come ashore at once to lay their eggs. Most commonly found in the Gulf of Mexico, this elusive species has sparked curiosity for decades due to its limited range and unique life cycle. In this blog, we’ll dive into the biology, behavior, and remarkable characteristics of the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle.

Appearance

The Kemp’s Ridley is the smallest of all sea turtles, with adults reaching about 2 feet in length and weighing up to 100 pounds (USFWS). It has a triangular-shaped head with a slightly hooked beak and large crushing surfaces, well-suited for its diet of benthic prey like crabs (NOAA Fisheries; USFWS). The carapace is oval and nearly as wide as it is long, typically olive-gray on top with a pale yellowish underside (NOAA Fisheries; USFWS). Each front flipper bears one claw, while the back flippers may have one or two (NOAA Fisheries). The shell features five pairs of costal scutes, and the bridges between the carapace and plastron each contain four inframarginal scutes, each perforated by a pore (USFWS). The head also has two pairs of prefrontal scales. Hatchlings are entirely dark or black on both sides (NOAA Fisheries; USFWS).

Behavior

Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles are marine reptiles that must come to the surface to breathe and exhibit a range of fascinating behaviors throughout their life cycle. After nesting on sandy beaches, hatchlings make a rapid journey to the ocean, where they enter a drifting phase, often associating with floating Sargassum algae. This algae provides food, shelter, and protection as they are carried by currents in the Gulf of Mexico or into the Atlantic Ocean via the Gulf Stream. This oceanic stage lasts one to two years, until the juveniles grow to about 8 inches in length. As they mature, Kemp’s ridleys settle into shallow coastal areas, where they primarily feed on crabs but may also scavenge on discarded bycatch. Adult males show a range of breeding strategies—some migrate annually between feeding and breeding grounds, while others remain near nesting areas. Females display remarkable navigational skills, returning to nesting beaches in Mexico and Texas, often in the same general area where they hatched decades earlier. Between nesting seasons, many females take up residence in foraging grounds across the Gulf of Mexico and return to the same areas year after year (NOAA Fisheries).

Diet

Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are opportunistic feeders, but their diet is heavily centered around crabs, especially blue crabs, which are considered their preferred prey (Mote Marine Aquarium; Chesapeake Bay Program). Once they recruit to shallow coastal areas, they rely primarily on these bottom-dwelling crustaceans, using their powerful jaws to crush and grind hard-shelled prey like crabs, clams, mussels, and shrimp (NOAA Fisheries; Chesapeake Bay Program).

While crabs make up the bulk of their diet, Kemp’s ridleys are also known to consume other available food sources, such as sea urchins, squid, jellyfish, and fish bycatch when crabs are less accessible (Mote Marine Aquarium; Chesapeake Bay Program). Their flexible feeding habits and strong jaw structures enable them to forage effectively along the ocean floor, taking advantage of whatever prey is readily available in their environment (NOAA Fisheries).

Range/Distribution

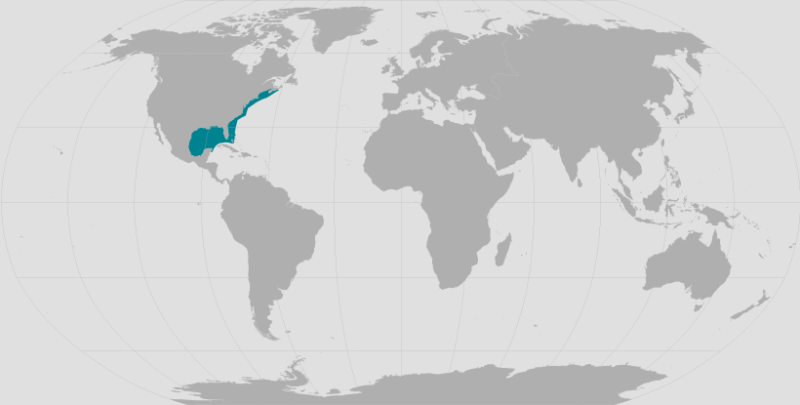

Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are primarily found throughout the Gulf of Mexico and along the U.S. Atlantic coast, ranging from Florida to New England (NOAA Fisheries). They are most commonly observed in nearshore and inshore waters, especially in the northern Gulf of Mexico, with Louisiana serving as a key feeding ground (NWF). These turtles prefer shallow coastal habitats with muddy or sandy bottoms, which support an abundance of their benthic prey such as crabs and other invertebrates (NOAA Fisheries; NWF).

In addition to their core range, a few records of Kemp’s ridleys exist from more distant locations, including the Azores, waters off Morocco, and the Mediterranean Sea, indicating occasional movement throughout the broader Atlantic Basin (NOAA Fisheries). Juvenile turtles spend several years drifting in the open ocean before settling in coastal areas, particularly estuaries and shallow seagrass beds, which provide food, shelter, and suitable conditions for growth. They typically remain in waters less than 160 feet (49 meters) deep, where foraging is most efficient (NWF).

Lifespan/Reproduction

Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are known for their rare and remarkable nesting behavior called an arribada, a Spanish word meaning “arrival.” During an arribada, large groups of adult females gather offshore and come ashore together in broad daylight to nest—an unusual trait, as most sea turtles nest at night. This synchronized nesting event occurs primarily on a single beach near Rancho Nuevo in Tamaulipas, Mexico, where approximately 95% of all Kemp’s ridley nesting takes place (NWF; NOAA Fisheries). Smaller numbers of females also nest consistently in Veracruz, Mexico, and at Padre Island National Seashore, Texas (NWF).

Nesting season typically spans from April to July, with females laying two to three clutches of about 100 eggs each. The eggs incubate for 50 to 60 days before hatchlings emerge, each weighing roughly half an ounce (14 grams) and measuring about 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) in length (NWF; NOAA Fisheries). Hatchlings instinctively move toward the brightest horizon—typically the ocean—using natural light cues on undeveloped beaches (NOAA Fisheries). Females return to nest every one to three years, often on the same beach where they hatched. Sexual maturity is generally reached between 10 and 15 years of age, and while exact lifespans are uncertain, Kemp’s ridleys are believed to live at least 30 years, possibly up to 50 (NWF; NOAA Fisheries).

Threats

Kemp’s ridley sea turtles face several significant threats throughout their life cycle. One of the primary dangers is bycatch, where turtles are unintentionally caught in fishing gear like trawls, gillnets, and longlines, often resulting in injury or death (NOAA Fisheries). Loss of nesting habitat due to coastal development, artificial lighting, and beach driving also poses a major risk, as it disrupts nesting behavior and can harm eggs and hatchlings.

Other threats include predation by animals like raccoons, birds, and crabs, vessel strikes near busy coastal areas, and ocean pollution, including the ingestion of or entanglement in marine debris such as plastics and fishing gear. Additionally, climate change impacts nesting success and hatchling sex ratios by altering sand temperatures and beach conditions, while also shifting food availability in the ocean (NOAA Fisheries).

From synchronized nesting events to their compact size and coastal lifestyle, Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles are a powerful reminder of the diversity and complexity found in our oceans. Their behaviors and life patterns reveal just how much there still is to learn about marine life. Whether gliding through shallow waters or emerging on a quiet beach to nest, the Kemp’s Ridley leaves a lasting impression on anyone lucky enough to encounter it.